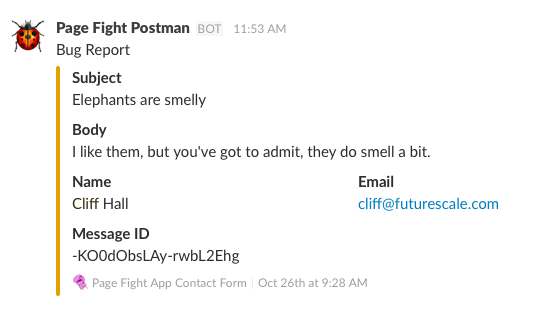

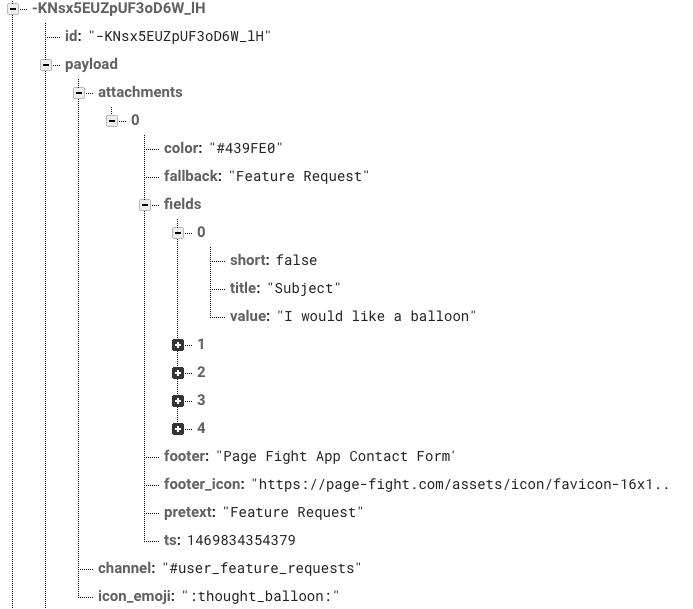

A nicely formatted Slack message

Just trying to get a message through

It’s no secret that Slack, the extensible group messaging service, has become the darling of development teams around the world for its ability to integrate documents, posts, and services from around the web. And if you’re working with Google’s hot new property Firebase as we are, you know it’s a blazing fast, ‘NoSQL’ database, offering its own application hosting solution. You can easily build and deploy your app using whatever frameworks you prefer, work with indexed JSON data, and support social sign-in with almost no effort.

Recently, on an application I’ve been building with this stack, I reached the point of needing to add a contact form. This seems like a fairly innocuous feature, since practically every site on the web has some sort of contact facility, usually including an annoying Captcha widget to deal with robot submissions.

But What If There’s No Back End?

The issue is, we’re not using a CMS and Firebase doesn’t provide a traditional backend. I suspect Google may provide one at some point, but that might conflict with their existing cloud platform, who knows? All I’m sure of is that there’s no backend at the moment, only an awesome database with fast static file hosting. Aside from this contact functionality, Firebase has provided everything my single page application needs.

I have a Perl CGI that I use on my company website, which sends me and the submitter a copy of the form by email. But since we’ve been using Slack for team communication, and literally all of our discussions and documents created since the project’s inception are collected there under one roof, we thought it would be nice if the results of our contact form went directly to a Slack channel. Or better yet, several channels: one for feedback, one for bug reports, and one for feature requests.

Slack Incoming Webhooks

So, the initial question was how to get a form submission on a Firebase webapp to post to Slack. Should be a no-brainer, because Slack provides a lovely interface for incoming webhooks. They’re drop-dead easy to set up, and the message display is nicely customizable, as you can see above.

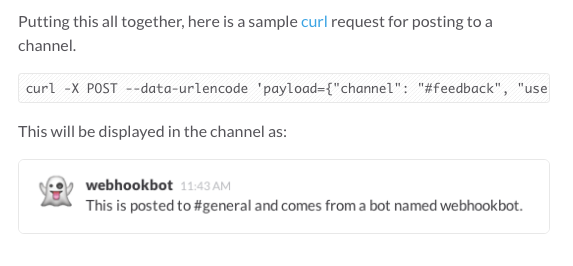

Once you’ve set up your incoming webhook, you get a special URL, which you can post to like so:

POST https://hooks.slack.com/services/T00000000/B00000000/XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Content-type: application/json

{

"text": "This is a line of text.\nAnd this is another one."

}

Easy-peasy, right? There’s just one problem: spamability.

Slack’s Best Practices for Integrations documentation says:

Do not share incoming webhook URLs in public code repositories. Incoming webhook URLs belong to a specific team member that installed them. When a webhook is contained within a Slack app, it is scoped to only post as a specific application-associated user and approved channel. Custom integration-based webhooks are capable of posting to any channel and have more flexible identities.

Compromised incoming webhook URLs can be used to post unwanted, unsolicited, or malicious messages to your team.

While I’m not planning to put my source code in a public code repo, anyone can open up Chrome Devtools and watch the traffic when they submit the form, thus revealing the super-secret URL. At first I wondered why they didn’t have URL whitelisting for this feature, but after a bit of research I came to the conclusion that there is no true way to do that.

They even offer a curl command to test the webhook with, and you can run it from localhost on your computer, which means it’s easily scriptable.

Any script-kiddie could spam the crap out of our channels in no time at all!

Playing ‘Hide the URL’

My first thought was to employ Node.js, running somewhere like Heroku, which would relay the message, thus hiding the Slack incoming webhook URL. Since a simple, one-line curl command could cause a message to show up instantly in a Slack channel, building a proxy that accepts the same post and bounces it to Slack should be a snap.

And it was.

I created a free account on Heroku, added a new ‘web dyno’ configured with the Node.js buildpack, slung a few lines of JavaScript (below), and had a simple proxy up and running in a few hours. I could run the same curl command that I was using to send a test message directly to Slack, except pointing to my new Heroku server, and bada-bing, my Slack client would notify me of my new message.

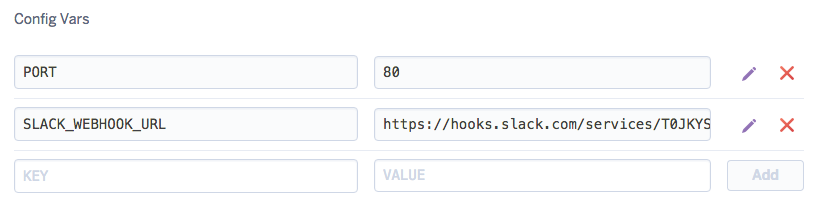

For extra points, I put the Slack URL and port number for the server in environment variables, which can be configured on the project’s Heroku dashboard.

Creating My Exclusive Club

My next step would be to add a whitelist capability, so that only posts from my application’s site would be accepted. And therein lies the rub.

The lack of CORS support on Heroku for Node meant that I couldn’t really do that. I could check the ‘origin’ header and bail if it wasn’t in the list, but of course, if all you have to do is put that header on the curl command, then it’s still vulnerable. Suddenly I realized why Slack hadn’t bothered trying to implement a whitelist, because only well-behaving browsers would obey it. For posterity, here’s what the first cut at this looked like….

// SLACK INCOMING WEBHOOK PROXY, TAKE 1

// GET THE SERVER PORT FROM THE ENVIRONMENT OR USE A DEFAULT

var port = process.env.PORT || 5000;

// CREATE SERVER AND LISTEN FOR REQUESTS

console.log('Slack Proxy: Creating Server');

var http = require('http');

var server = http.createServer();

server.on('request',handleRequest);

server.listen(port);

// HANDLE A REQUEST

function handleRequest(request,response){

console.log('Slack Proxy: Handle Request');

// SET REQUEST AND RESPONSE ERROR HANDLERS

request.on('error', function(err) {

console.error("Error" + err);

response.statusCode = 400;

response.end();

});

response.on('error', function(err) {

console.error("Error" + err);

});

// VALIDATE THE ORIGN DOMAIN AND BAIL IF NOT WHITE-LISTED

// Aww snap...

// Turns out this is a non-starter, because origin header can be spoofed easily.

// Otherwise, this is a perfectly fine proxy, if you don't mind just ANYONE calling it.

/*

var origin = request.headers['origin'];

.

.

.

*/

// RECEIVE THE BODY OF THE REQUEST

var body = [];

request.on('data', function(chunk) {

// PUSH A CHUNK

body.push(chunk);

}).on('end', function() {

// REACHED THE END

body = Buffer.concat(body).toString();

// HANDLE ROUTES

if (request.method === 'GET' && request.url === '/echo') {

// ECHO DATA BACK (FOR TESTING THAT SERVER IS UP)

handleEcho(body,response);

} else if (request.method === 'POST' && request.url === '/') {

// PARSE DATA AND SEND TO SLACK

var payload;

try {

payload = JSON.parse(body);

} catch (err) {

response.write("Error: "+ err);

response.end();

}

if (payload) sendSlackMessage(response, payload);

} else {

// UNSUPPORTED ROUTE

response.statusCode = 404;

response.end();

}

});

}

// ECHO THE REQUEST DATA ON THE RESPONSE

// curl -X GET -d 'Hello World' http://localhost:5000

function handleEcho(body,response){

console.log('Slack Proxy: Handle Echo');

response.statusCode = 200;

response.end('\n'+body+'\n');

}

// SEND A SLACK MESSAGE WITH THE REQUEST DATA

// curl -X POST -d '{"channel": "#feedback", "username": "CliffBot5000", "text": "This is posted to channel #feedback.", "icon_emoji": ":ghost:"}' http://localhost:5000

function sendSlackMessage(response, payload){

console.log('Slack Proxy: Handle Slack Message');

// GET WEBHOOK URL FROM THE ENVIRONMENT

var webhook = process.env['SLACK_WEBHOOK_URL']

// IF WEBHOOK CONFIGURED AND PAYLOAD PRESENT, FIRE AT WILL

if (webhook && payload) {

// CREATE REQUEST MESSAGE

var message = {

uri: webhook,

method: "POST",

json:true,

body:payload

};

// MAKE THE REQUEST

console.log('Slack Proxy: Sending Slack message...');

var slackReq = require("request");

slackReq(message);

response.statusCode = 200;

} else {

// REPORT ERROR IF WEBHOOK NOT CONFIGURED OR PAYLOAD NOT PRESENT

response.statusCode = 500;

}

// ADIOS MUCHACHOS

response.end();

}

Back to Square One?

With the whitelisting proxy idea dead in the water, I began to think about Firebase and its authentication system. It has no backend for me to run Node on, but it is super at protecting the database with a ruleset that matches its structure. If I could somehow create a message queue in the database, and then have a scheduled Node.js script process the messages and send them to Slack, I’d be in business. As long as a secure channel could be created between Heroku and Slack that is.

I have the entire database protected so that users must to be authenticated to access anything at all, since I don’t want anyone ripping my database and taking protected user info like email addresses. Even authenticated users can only see parts of other users’ profiles.

But in this case, I wanted anyone to be able to contact us, whether they’re logged in or not. Still, I didn’t want someone to be able to script a spam attack, so there had to be some level of authentication.

That was when the big light bulb switched on over my head and all was illuminated.

Previously, I’d implemented social sign-in on all of Firebase’s supported providers (Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Github), as well as the email/password provider. But there is another type of authentication on offer, which up until then I’d seen no use for in my app: The Anonymous Provider. This is intended to let users start interacting with your site and using its features (for instance, uploading and manipulating an image), and then later convert to a registered user if they wish to save their data or access more features. That, I thought, could be just what the doctor ordered.

Building the Mailbox

In Firebase, I created a special account with an email and password which would only be used to log in and pick up the messages. This yielded a user ID that I could then use in my database ruleset to ensure that only that user could read AND write to the message queue (to mark messages read when they’ve been processed). All other users would be able to write to the message queue, but not read it. I also added the requirement for a boolean ‘read’ flag, and created an index for it. This would allow the Postman script to fetch only messages that hadn’t yet been read.

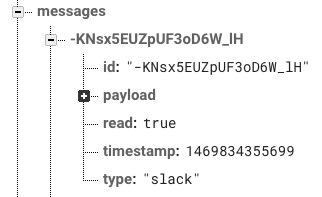

A special Firebase ruleset for the messages node in the database.

Creating Messages

My Custom JSON message format. The payload could vary based on message type.

In the database’s new ‘messages’ node, I’ll be storing JSON objects.

On each message is the payload that goes to Slack (with it’s own internal structure), and also some meta-data about that payload, which my Postman script will use to mark the message as having been read, and also to determine how to handle the message, once the system grows to do other things with messages than just send them to Slack.

As you can see at the top of this article, Slack supports advanced message formatting. Basically, there is a payload object, which contains an attachments array, with each attachment (only one was needed for my purposes) containing message level data like the icon_emoji and title (duplicated as fallback and pretext), and a fields array. The fields array contains the various parts of the message, with each field having a title, a value, and a short flag that says whether another field can be shown beside it (true), or if it should reside on a line by itself (false).

The payload of a Slack-bound message

Enter the Postman

I created another Heroku Node.js dyno, and threw in the Heroku Scheduler add-on. This time, the script was not a continuously listening webserver, but instead, a scheduled process that:

- Runs every ten minutes

- Logs into Firebase with a special email and password I set up for it’s sole use

- Reads the message queue with a query that fetches only messages that haven’t been read

- Processes the messages according to type (by this point I was already envisioning this process handling other kinds of messages than the Slack-bound sort)

- Calls the appropriate handler method for each message (resulting in messages of type ‘slack’ going to the appropriate Slack channel)

- Sets the message as read in the Firebase database, where it will be preserved but not fetched again by the Postman)

// SLACK INCOMING WEBHOOK PROXY, TAKE 2 - THE POSTMAN

// REQUIRED MODULES

var firebase = require('firebase');

// THE POSTMAN ONLY RINGS ONCE

signIn();

// SIGN IN AND CONNECT TO THE DATABASE

function signIn(){

console.log('Signing in... ');

var email = process.env['FIREBASE_USER'];

var password = process.env['FIREBASE_PASSWORD'];

var url = process.env['FIREBASE_URL'];

var db = {};

db.base = new Firebase(url);

db.messages = db.base.child('messages');

db.base.authWithPassword({

email : email,

password : password

}, function(error, authData) {

if (error) {

console.log(error);

} else {

console.log('Success!\n');

fetchMessages(db);

}

});

}

// FETCH THE MESSAGES

function fetchMessages(db) {

console.log('Fetching messages... ');

var messages = [];

db.messages

.orderByChild('read')

.equalTo(false)

.once("value", function (snapshot){

snapshot.forEach(

function (childSnapshot) {

messages.push(childSnapshot.val());

}

);

// IF THERE WERE PENDING MESSAGES, PROCESS THEM

if (messages.length) {

console.log('Processing ' + messages.length + " pending messages.\n");

processMessages(messages, db);

} else {

console.log('No pending messages.\n');

process.exit();

}

});

}

// PROCESS RETRIEVE MESSAGES, HANDLING EACH BY TYPE

function processMessages(messages, db){

var i,message;

for (i=0; i<messages.length; i++){

message = messages[i];

switch (message.type) {

case 'slack':

sendSlackMessage(message.payload);

markMessageRead(message, db);

break;

}

}

}

// SEND A MESSAGE TO SLACK

function sendSlackMessage(payload){

// GET THE WEBHOOK URL FROM THE ENVIRONMENT

var webhook = process.env['SLACK_WEBHOOK_URL'];

if (webhook && payload) {

// CREATE THE REQUEST MESSAGE

var message = {

uri: webhook,

method: "POST",

json:true,

body:payload

};

// MAKE THE REQUEST

console.log('Sending Slack message...');

var slackReq = require("request");

slackReq(message);

}

}

// MARK THE MESSAGE AS READ IN THE DATABASE

function markMessageRead(message, db){

console.log('Marking Slack message read...');

var node = db.messages.child(message.id);

message.read = true;

node.set(message);

}

Conclusion

Is there more to be done with this script? Certainly. What if Slack is down? We need to make sure that we don’t mark the message as read until we’ve received a response from the request. Also, I plan to support more message types that trigger different interactions between the Postman script and the database (which is why the switch statement is used when processing each message). But all in all, this is a much better solution than the original, brute force proxy approach. The addition of message types allows for expansion of the Postman’s responsibilities, something I’d already identified as necessary in future development sprints anyway.

Are you using Firebase, Node, and Slack? If so, then perhaps this integration approach will work for you. Let me know what you think in the comments below!

This article has been reblogged at the following site:

DZone: https://dzone.com/articles/securing-slack-webhooks-with-firebase-and-nodejs