Ah, the thrill of being first to market. Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash

Getting Our Fix

I’m going to reveal a deep, dark, and personal consumer secret: I love Reese’s Dark Chocolate Miniature Cups. So does my wife. They’re our go-to treat, snack, dessert. We never run out of them.

Almost never.

I say this because recently, an inexplicable thing happened. All of the stores we visit that carry them ran out. And they didn’t stock back up for ages. Like months.

Sometimes this happens to a product if a rebrand is happening, and I get that. But we needed those things. Our lives were upside-down with out them. So we went online and found a vendor on Amazon (who shall remain nameless) that had them in bulk. Plus, they were far cheaper that way. Of course, we ordered with express shipping.

The Pretender to the Throne

Later that week, our monster bag of Reese’s Dark Chocolate Miniature Cups arrived, and we probably ate twenty of them in the first day. Ok, maybe less. Definitely more than our caloric budgets allowed for.

But they didn’t taste quite like we remembered.

We thought they might be stale or perhaps had sat in a hot warehouse or delivery truck for too long. The inner wrappers didn’t peel off so easily and tended to tear the confection on removal.

But don’t get me wrong. They were OK. I certainly didn’t toss them out. Even after we started seeing them in stores again and stocked up.

Genuine Goodness Reigns Supreme

When we compared them, we could taste the difference immediately. The faux cups had come in a clear plastic bag with a laser-printed label that claimed we were getting the genuine article. We had just figured that Reese’s didn’t bother with the outer bag so much when they sold in bulk. But upon closer inspection, the outer wrappers gave the pretender away.

We’d bought knock-off chocolates. Doh! That’s why they were so cheap.

Wait though. Why?

They weren’t that bad, they just weren’t Reese’s. We had certain expectations and they weren’t met. But they’ll do in a pinch.

My question is two-fold. Why were they so cheap? And why even bother with a knockoff if you’re capable of something so close to the original?

The counterfeiters had gone to great lengths to create a chocolate and peanut butter confection, molded by a tiny muffin wrapper, and delivered in a printed aluminum foil overwrap, just like the widely known and loved classic. They just didn’t have the recipe perfected.

That tells me they had a lot of resources at their disposal. They could have instead created their own unique confection, sold it on its own terms, and charged more for it. It would have been judged on its own merit rather than being compared directly to a known and popular product and found lacking. What’s more, they didn’t make anything close to Reese’s prices with their under-handed skeevery. Sure, they get the benefit of an established market with a very specific desire, so they don’t have marketing overhead. But the deep discount in price would seem to offset that win entirely. So again, why???

We may never know the answer to this conundrum, but it leads me to the point of this essay.

Where Creators Focus Their Efforts

To be honest, as a longtime entrepreneur who has never had a tremendous amount of success, I continually find myself wondering why I even try. I have skills, that’s not the problem. When I’m executing on a client’s vision, I have no issues turning in solid work that goes above and beyond the requirements. It’s just that my own projects never really seem to catch fire.

Why so fail? Photo by Karina Carvalho on Unsplash

I will cede that I generally don’t follow through on marketing. There is rarely spare time to put into new projects, much less money laying around to market them. As a result, I have a tendency to “push a project off the loading dock” when it’s done and move on. I’ve also had times where the effort to complete the project was much greater than expected going in and I had to park it on a sidetrack.

So, I’m not scratching my head too vigorously about why I don’t get traction.

But there is another thing that’s common to most of my endeavors, and that is that they are generally “greenfield” projects. The big idea that no one else has done yet. A wide open market! And I see this trend with a lot of the creators I know or follow.

We are going to totally disrupt how market X works!

Given a certain amount of talent and resources, most startup founders seem to want to do something unheard of. Make their mark on the world. And yet 75% of venture-backed startups fail. This is why I don’t fret lackluster returns on my own un-funded efforts that much.

The Bob’s Burgers Strategy

The thing that the imposter chocolates has made me consider is whether doing something totally new is a great use of my time, considering I’m not independently rich. Do I have to disrupt an entire industry? Must I find a way to turn an under-served niche into an overnight success?

Or would it be OK to just find a market that already has a few big players, and figure out how to deliver something substantially similar at a cheaper price? If I could make a little money that way, I might be able to fund development and marketing for the next greenfield project.

I’m not endorsing fake peanut butter cups intended to dupe consumers into believing they were buying something else. That’s just wrong. I’m simply suggesting that building a competitor to an existing product, if it’s easy enough to do, couldn’t hurt. It wouldn’t be sexy, but it might be profitable.

With a McDonalds on nearly every American street corner, could Bob’s Burgers still turn a buck selling regular fries?

Even though Amazon, who began as a bookseller, has probably the largest selection of eBooks in existence, it doesn’t put Kobo out of business. In fact there are probably enough diehard “Never Amazon” consumers out there who simply don’t like the behemoth’s market domination that they’ll shop Kobo out of spite. Even if they have to pay more.

And what about that last bit? Does a fledgling competitor in an existing market necessarily have to undercut the prices of the established players?

Low, Low Prices

I listen on the reg to a podcast called MegaMaker by Justin Jackson. He’s a super-energetic bootstrapper and (as far as I can tell) has no fear of failure. His podcast used to be hosted on Simplecast.fm but now its on Transistor.fm, which just happens to be his own startup. When I noticed this change, I thought, “Aha! He’s figured out how to do it himself and charge less.” Go Justin.

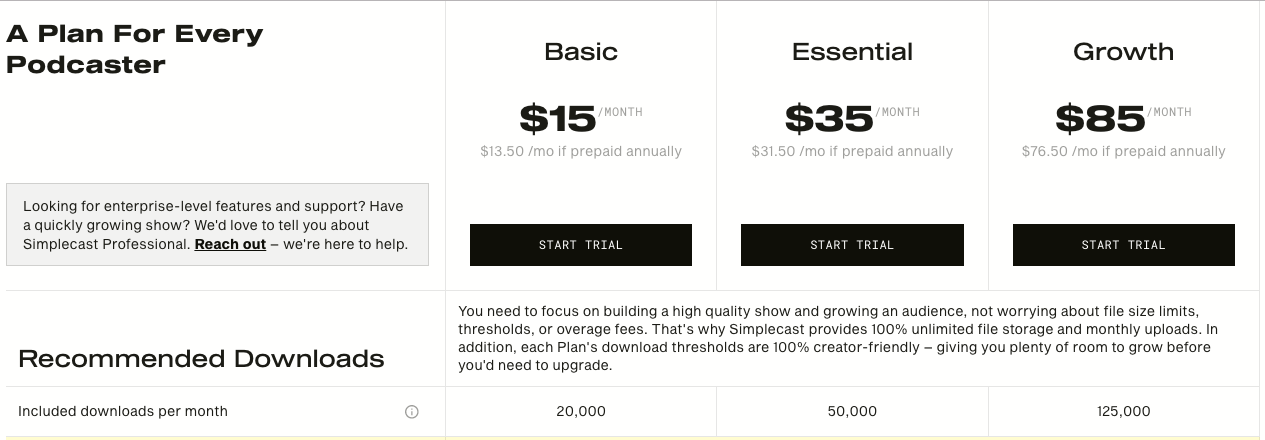

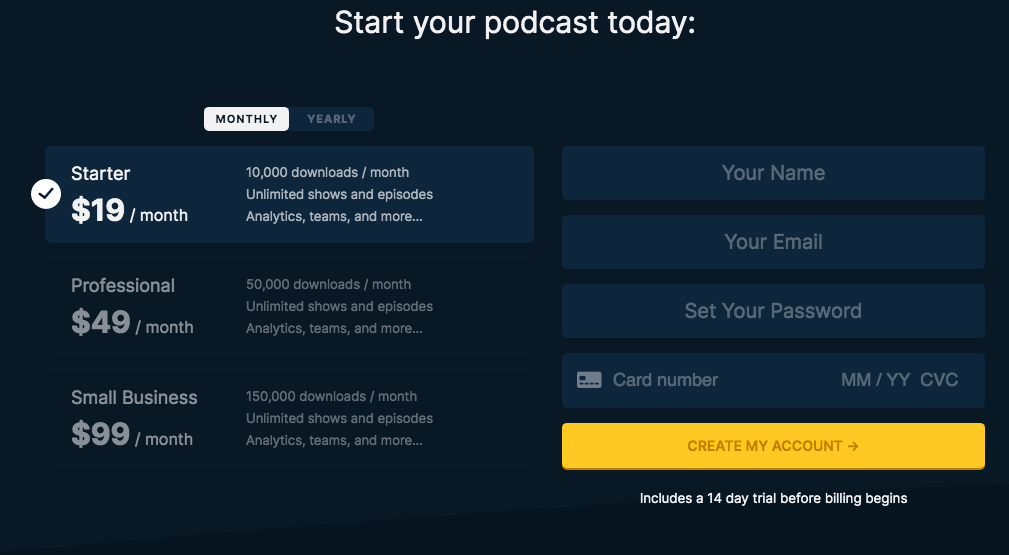

But then I took a look at the product pricing pages for both platforms. Have a look:

Simpecast.fm pricing page

Transistor.fm pricing page

You’ll notice Transistor is actually more expensive on all tiers. On the low tier, they give less downloads, on the medium they match, and on the top tier they offer a little more. Of course downloads isn’t the only metric, but still, this blew my mind.

I caught up with Justin on Twitter and asked him about it. He definitely had plenty of experience as a podcast hosting customer.

I’d tried multiple podcast hosts before I launched Transistor, yup. – Originally self-hosted on WordPress – Then, self-hosted on AWS – Tried Soundcloud – Then used Simplecast.

I asked him how he’d arrived at the pricing strategy, and he had this to say:

Pricing is hard! We started by seeking out advice from some pricing experts, folks like Patrick Campbell, Ruben Gamez, Nathan Barry, and Rob Walling. We did three episodes of our podcast during that initial discovery time. Then, we revisited our pricing again recently.

This led down an extremely nuanced rabbit hole, the twists and turns of which every founder should familiarize themselves with. Essentially, it comes down to understanding the value that your customer feels they’re receiving for the price they pay and whether you’re leaving any value “on the table.” Are you charging every penny you can get? Or is there room for the customer to feel like even if you raised your prices, they’d stick with you because the value proposition is so strong? It’s way more complex than that, of course, but the point is: “charge more” or “charge less” can both work depending on product/market fit.

If this is a topic that interests you, I suggest following Justin’s thoughts on the matter. He’s proved that you can enter an existing market, provide a similar product and be successful, even if you’re not the cheapest game in town.

- [Podcast] How should we price our SaaS?

- [Podcast] What does Nathan Barry think of podcast hosting pricing?

- [Podcast] SaaS pricing advice from Rob Walling and Patrick Campbell

- [Podcast] The “charge more” debate

- [Article] Should we always charge more?

A slightly tangential but extremely important point that Justin brought up in our conversation was that, be it greenfield or existing, the market you enter will dictate a lot of your success. Its size is a multiplier for both opportunity and difficulty of standing out and being heard. Read more about that in his article How do I build something people want?

Conclusion

As founders, we don’t necessarily have to identify “greenfield” opportunities and rush to be first to market. In the words of a wise old salesman at a startup I worked at before “startup” was even a thing companies called themselves:

Don’t worry about being first. Someone with more funding and resources will just come along, duplicate your work, and eat your lunch. I’d rather be second and be better.